The Politics of Work/From Strike to Revolution: The Politics of Work and Work Refusal (Spring 2025, Fall 2025)

I taught a version of this course at the Fishkill Correctional Facility as part of the Bard Prison Initiative in Spring 2025 and a version of this course at Bard College’s main Annandale Campus in Fall 2025.

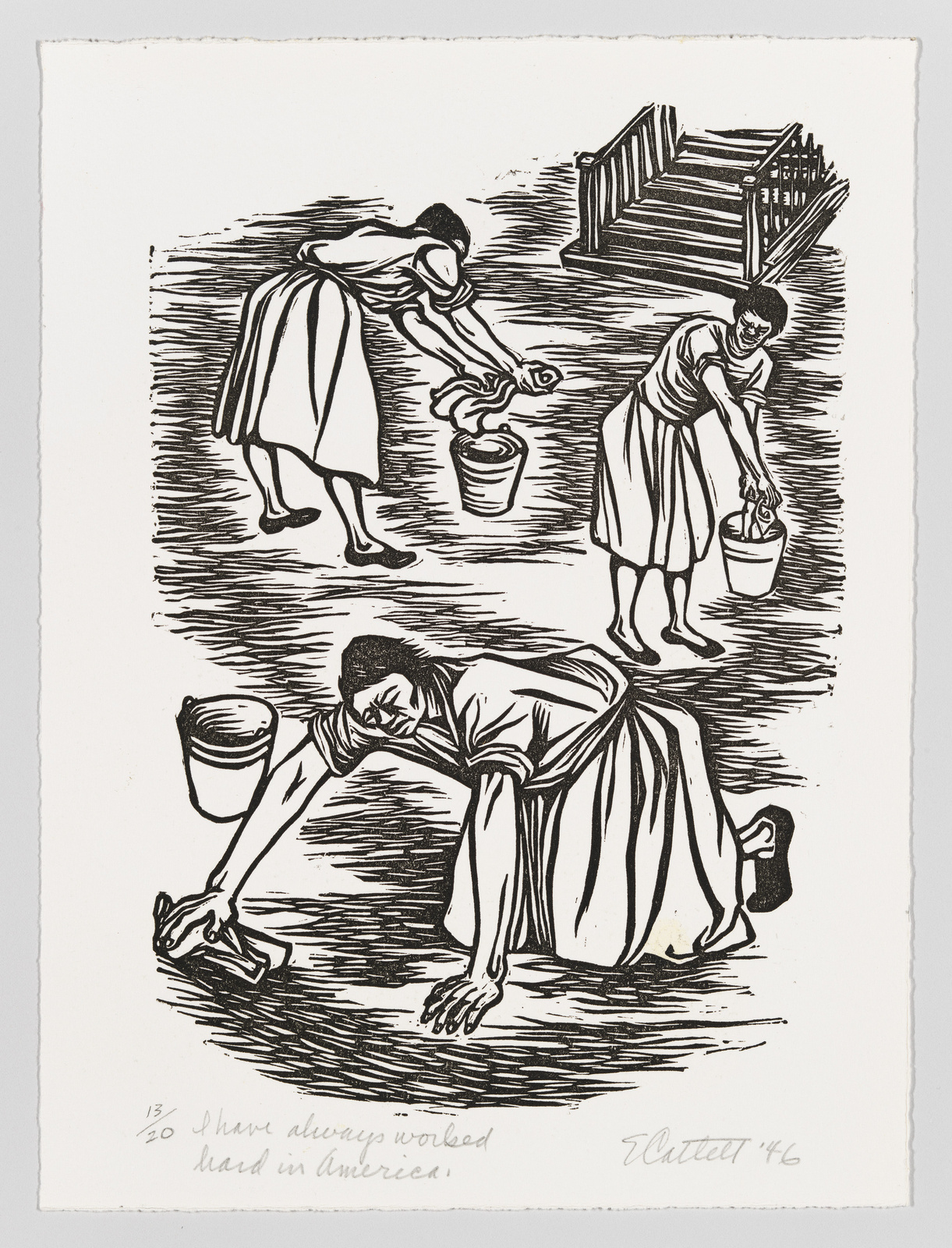

Course description: Most of us spend over a third of our waking lives working for a wage. Many of us also perform unwaged work, for example, taking care of ourselves and our loved ones. Does decent work provide our lives with meaning and thereby promote human flourishing? Do we work just to survive? Or is work merely a “mechanism by which individuals are incorporated into the capitalist mode of cooperation” (Kathi Weeks)? And if work is neither necessary nor a social good, how might work be transformed—or even abolished? In this course, we explore answers to these questions by reading works of political theory, labor history, and literature, with particular attention to the critical interventions of workers’ movements, as well as feminist movements and the Black Radical Tradition. Beginning with a survey of theoretical perspectives on work, we then turn to political movements to transform our working life. Finally, we consider the effects of automation on work and the possibility of a society free from work. We will read texts by John Locke, Karl Marx, W.E.B Du Bois, Hannah Arendt, James Boggs, Angela Davis, and others.

First-Year Seminar II: Machiavelli (Spring 2026)

First-Year Seminar II is a unique course taught in the Bard Prison Initiative degree program, in which students carefully read one or two classic texts in a particular discipline across the course of the entire semester, along with secondary literature. I chose to teach this course on Machiavelli’s oeuvre.

Course description: To be “Machiavellian” is, in common parlance, to be willing to do anything to hold onto power—one prominent philosopher calls him a “teacher of evil.” Indeed, Machiavelli writes in his classic book The Prince—the first book we will read in this class—that in order to rule effectively one must learn “not to be good.” And yet Machiavelli says he wrote The Prince from the perspective of the people. Moreover, he himself was politically active in his native Florence at the turn of the 16th century, and tried to save the institutions of the Florentine republic from being taken over by wealthy oligarchs. Machiavelli saw the Roman Republic as a great resource for understanding these events, and wrote a commentary on the work of ancient Roman historian Livy, Discourses on Livy, which we will also read in this class. Additional texts include Machiavelli’s History of Florence and several plays he wrote. Machiavelli is among the most influential—and ambiguous — writers in the history of political thought. As one scholar put it, “Machiavelli will reveal himself only to those willing to listen to him, that is, to read his books attentively”—which is exactly what we will aim to do.

First-Year Seminar: The Republic Revisited (Fall 2024)

All of the first-year students at Bard College take First-Year Seminar (FYSEM), a “great books” course that also aims to build skills in reading and writing. Each student is part of a section taught by one of the twenty or so FYSEM instructors, each of whom is given a list of core texts based on a theme around which to construct a syllabus of their own making.

Course description: First Year Seminar aims to educate you about the intellectual traditions that have shaped many of the societies we live in, and to give you tools that can help transform these societies. The Fall semester takes Plato’s Republic as an anchoring text to focus on the idea of the state as a commitment to organizing society, and to political life as a shared endeavor. Over the semester you will read texts from the classical period up to today. These texts present an enormous diversity of theories about the human being as creature, as self, and as citizen. Through exploring different explanations of how individuals come together to form a civic body, we will bring the contingency of our contemporary practices into view. We will track the power struggles between political, religious, and scientific authorities through the centuries that can help explain those of the present day. We will consider how definitions of “self” and “other” contribute to structures of power, oppression, and liberation. We will trace changing conceptions of human nature: of our differences from non-human animals, of our capacities to care for each other, of the boundaries of our rights and freedoms. In order to address these problems of living in political community, we will also cultivate the skills needed to participate in a democracy: the capacities to question authority, to disable ideology, and to think critically and creatively about the challenge of living among others. Rather than remembering names or dates, your task is to analyze the arguments, stories, and poetics put before you and to relate them to each other, and, ultimately, to come to your own conclusions about the questions at hand.